Authentic Play and the Undiscovered

Yikes, what a title. Save it for the book, am I right?

This is quite a long one, as it takes on quite a few points and blog posts. But there are some insights here, both from others and, I hope, from me.

🕷

Authenticity

The Glatisant rolled around again, and fed me a slew of new blog posts. Chasing them down the rabbit hole, I found a discussion of FKR and OSR methods of play that focused on the interesting concept of authenticity.

The best way to define authenticity is probably in contrast to its opposite, illusionism. This concept, from Hack and Slash, is exemplified by a technique called the quantum ogre: The players go left, they face an ogre encounter; the players go right, they face the same ogre encounter, because it's what the GM has prepared. Even if you haven't heard of it in those terms, you'll probably have played at a table where the technique was used. The idea is that the GM has crafted an experience for the players, here involving an ogre encounter, and the facts of the game world are bent to fit the play experience to this intended one, or are left indeterminate, the better to introduce the intended play elements.

Authenticity means placing the ogre in a particular place, determining where the party would have to be in order to encounter it, and then not springing the encounter if they don't go there. Alternatively, you could place the ogre's lair, and determine a percentage chance that it will be there if the party stumbles onto it. Provided you abide by what the dice tell you, and don't, say, vary whether it's in the lair depending on what you think would be most dramatic, that's playing authentically.

In short, playing authentically means knowing about the world the characters are exploring, and not fudging anything because you think it'll be more fun, or any other related reason. For more discussion, and the coining of this particular usage of "authenticity", see this illuminating article by Tim B.

In the article, Tim posits that the authentic style is what characterises OSR play. I'm always wary of trying to reduce the OSR down to one particular approach - that project always seems to have met with failure in the past - but this seems like a strong contender. For one thing, it captures the idea of the referee as a neutral arbiter that we see in such ideals as "combat as war" and "no fudging". Tim covers how this allows the game to present an authentic challenge, because the players know that they aren't being spoon-fed a victory.

This is very interesting, and I want to build on and deepen the points made there.

🕷

Authenticity underpins exploration

I want to flag up an interesting boon that authentic play guarantees for the OSR that I haven't seen given much coverage, but that seems even more central to the OSR than challenge. This may be a subjective assessment, because this is the thing, above all else, that draws me to the OSR, and indeed roleplaying in general. That thing is exploration.

D&D is often sold as a game about exploration. This has been true from the time of dungeon and wilderness exploration in the 70s and 80s, all the way up to today, when exploration is explicitly listed as one of the three key pillars of D&D gameplay. Despite its importance to the format (I'd argue it features very heavily in the imagined game) the modern playstyle of D&D struggles to provide this form of engagement. One of the perpetual worries for 5e GMs is how to make exploration feel like exploring.

What you get is a lot of "missing ingredient" answers - describe things in such-and-such a way, ask parties to detail what they're doing to pass the travel time, or to rp their fireside chats, play a minigame, etc etc. In fact, I think the missing ingredient is both more and less obvious than these patches: A group will feel like it's exploring if they believe that what is out there to be discovered is out there, and will remain there whether or not they discover it.

This, after all, is the essence of discovery: There was something there that you didn't know about, and you found it. You could have failed to find it, so in that sense, it was a success - fair enough, we know authentic play underpins authentic successes. But it also makes it personal: Another group sitting at the table on a different night might not have found it, either because they chose a completely different direction, or because they got unlucky or whatever. It's not just an achievement, it's your achievement. The experience is one shared by your group, but unlike a scripted adventure, which plays out in broadly the same way whoever sits at the table, it's unique to your group.

(Note that this applies even to bespoke, home-grown adventures a GM only intends to run once; even though the group knows no-one else will likely ever play it, they don't feel ownership of the outcome, because they know they could have been replaced, and the experience be largely the same - see my post on War Stories for more discussion.)

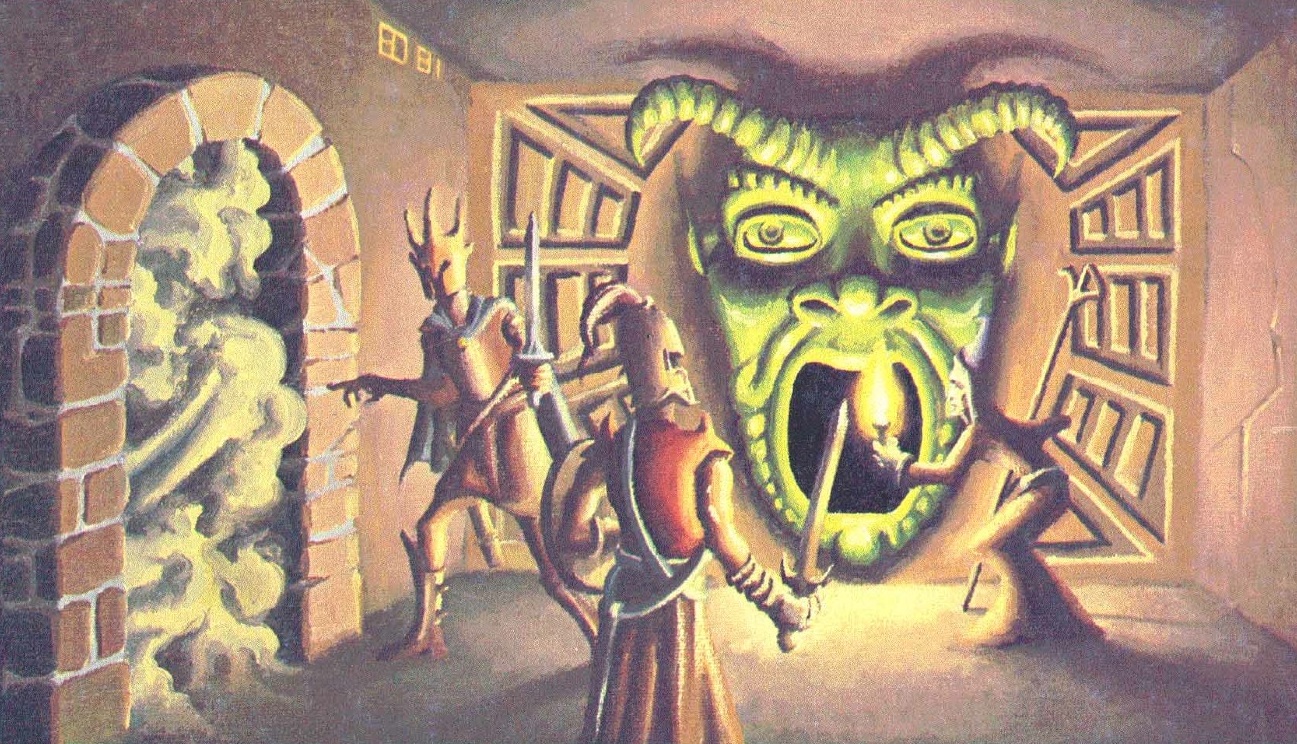

What makes finding a secret door in a dungeon or an interesting landmark in a hexcrawl meaningful (to use a fluffy word) is the knowledge that you might not have found it, had you done things differently. But more than that, it tells you that there are other things out there that you haven't found, and that possibility is what draws one to explore in the first place. In a world where you know that the important things will track you down, quantum-ogre style, regardless of your actions, there is no meaningful exploration because there is simply nothing to find - anything as-yet unfound will find you.This tells us, incidentally, why the archetypal OSR adventures are dungeons and hexcrawls. When you get down to brass tracks, these actually aren't adventures at all - they're environments detailed by or for the GM. There's nothing in the format of the dungeon or the hexcrawl that will chase the players down - if the players miss something, it stays missed. And it's knowing that, as a player, that makes the stuff you have found feel special, and the rest of the world feel mysterious and tantalizing, and ripe for exploration.

🕷

Authenticity underpins engagement

If there's one evergreen discussion on D&D Reddit, aside from GM burnout, it's the problem of getting the players to engage with and care about the world. And I want to say that authentic play is the answer, or at least the greater part of it.

Imagine the following: You're running the classic old school, open table megadungeon campaign. Abby's party has been adventuring for months, taking the same route past the statue of the Cat Goddess each session, as a quick way into the midst of the complex. One session, Abby finds herself adventuring with Bert's party, with whom she hasn't played before. She recommends the Cat Goddess route, and they take it. At the statue, Bert remembers that his character has some milk on him, so he pours some into the bowl held by the statue - cats like milk right? - for good luck. To everyone's surprise, the statue grates aside, revealing a secret room containing a mummified body wearing the Aegis of Bast, a magic item.

"Holy crap," thinks Abby, "I've walked this way a million times and I never knew that was there!"

It's a cute story, but there is a point to it: What makes the world feel like a real place is the knowledge that there is stuff in it you don't know about. And that's not just the fantasy world of the tabletop - that's what underpins our sense of the real, as opposed to the illusory or hallucinatory, in the actual world. This is the difference between the real world and a dream that feels irreal because the only things that happen are the things happening to you. The real world feels real because you know that there's stuff that's unseen - there's more to it than meets the eye.

But there's a problem here, namely, how can you create in me the sense that there are things I'm not being shown, if all you can do is show me things? Or, put another way, how can an experience give the impression that there are things that have not been (and may never be) experienced?

Again, this isn't just a problem for the tabletop - this question comprises several branches of Philosophy. And there are people who answer, simply, "You can't". As in, the only things that are knowable are experiences, and you can't have experienced something that hasn't been experienced (Philosophy is full of illuminating insights like this). Therefore, it's pointless, or even impossible, to talk about anything beyond what you actually experience.

The quantum-ogre GMs are in this camp, philosophically speaking, with the idealists and radical empiricists: The players only experience what actually hits the table, therefore what does it matter if I futz the encounters? They went the way they went - they don't know that it would have been the same if they'd taken the other path. They didn't experience it.

As philosopher Edmund Husserl points out, this misses the point. There are ways to structure experience to furnish the concept of a world that extends beyond that which we perceive - the evidence for this is the fact that we have such a concept of independent reality at all. For our purposes, the point is this: What the GM has to do is to demonstrate that they are willing to let the players not experience something. This is what the story of the Cat Goddess statue is supposed to show - that by setting the precedent that you won't spoon feed content to the players, that you're prepared to keep some secrets to yourself, perhaps forever, you create the sense of the game world as a real place containing facts of its own, independent of those presented to the players. This gives the world a "thickness", instead of that thin, holographic quality it takes on when the players are convinced that, like in a dream, the only things that happen are the things that happen to them.

The assumption buried in the quantum ogre and similar techniques, that all that matters is what gets experienced, actually robs the world of a lot of its nuance. Experiences, even in the sense of content experienced in an rpg, have structure. For instance, the experience the group has of finding the secret door in the story contains the embedded structure consequence of our experimentation, a causal structure that situates it within a chain of cause and effect. More pertinently, when Abby reflects on never having found the secret before, she inserts it into her memories of play as having the structure yet to be discovered. The latter is the operative one for getting players to engage with the world as something that holds secrets, as opposed to a machine that vomits forth content - you need the content to demonstrate, by the way that it is hidden/found, that it could have been missed, and would have been, but for the players' actions.

As a further illustration, look at the common variation on "My players aren't engaged in my world" that goes "My players don't care about my NPCs." Consider that, in Philosophy, idealism tends to breed solipsism - if all that exists is the stuff that I experience, then other people (meaning other minds) don't exist, since their inner lives are beyond my ability to experience directly. In the real world this is solved for by the structures of experience mentioned above: Just as experiences with structures like yet to be discovered point beyond themselves to a world that is not perceived, in the same way experiences of people have structures (such as part of an ongoing plan or reaction to past trauma) that point beyond the experiences themselves to the other person as an independent being with an independent life.

In game terms, this means that NPCs don't feel like real people worth taking an interest in if they exist only to advance the plot. If NPCs only react to the players, and act inconsistently depending on the demands of the plot rather than their own internal drives, the players will naturally treat them as vehicles for game content rather than people. If you make it clear that the NPCs are beholden to drives that have nothing to do with the players, will undertake actions "offscreen" and so on, then the players' interactions with the NPCs will point towards their having an independent existence that it's worth taking an interest in, analogously to how the Cat Goddess example shows there are genuine secrets, and that it's worth experimenting to find them.

(As an aside: Husserl calls this phenomenon of an experience pointing to something beyond itself "apperception", meaning perceiving without perceiving. I find it wonderful that the OSR, in its advice on NPCs in particular, has essentially re-engineered this arcane philosophical concept.)

What quantum ogre play does is flatten gameplay experiences, denying that they have this level of structure - the only thing that matters is what content gets presented to the players, not how it is presented. But this denial is a chief culprit in discouraging player engagement. Players playing in a "quantum ogre environment" are trained to let the content come and find them. Everything they know of the game reinforces the idea that the only things that exist are the things they experience. They have no reason to engage with the game world like a real place, in the sense of probing it for facts beyond their knowledge, because there are no such facts - the facts will be manipulated and presented to them as required to convey the prepared game content.

Hence players learn passivity; there's no point in taking an active interest, because the play experience will hunt you down anyway - even if you're able to glean anything from your investigations, the information won't end up affecting anything you actually end up doing. Essentially, it's yet another form of Abused Gamer Syndrome.

🕷

Authenticity and Accountability

Idiom Drottning posted a very interesting (and evolving) article on trust in FKR games. The conclusion pertinent to this discussion is that immersion is built through trust - trust that the GM is presenting things as they are in their notes, not fudging dice rolls and so on. This creates what they term "buy-in immersion", as opposed to "mood immersion" (what I've called "fog-machine immersion" in the past); you're immersed because you're invested in some aspect of the game, e.g.: in the continued survival of your character, not just because you're simulating some sensory aspects of the game world.

If I may say, and in the nicest way possible, I think the author is displaying their own distinctive version of Abused Gamer Syndrome. Certainly, rolling in the open is a popular practice now, but the idea of stopping the game to show the players your notes and verify enemy counts etc. so they believe you won't mislead them seems like something one would only think necessary if one had developed trust issues from previous gaming experiences, which, per the article, seems to be what happened; Idiom Drottning (I have no idea how to credit them as an individual, willing to be informed or corrected) played a lot of games in their developmental rpg years that were explicitly fully improvisational, and therefore fell into a lot of the traps listed above.

Let me expand on that point a little. When a game is explicitly improvised by the GM at game time, you know that every encounter is a quantum ogre encounter, every trap a quantum trap etc. Hence application of any of the structures of experience in the previous section to your gaming experiences will be artificial; you know that for your character that secret existed in a yet to be discovered state, but for you, that wasn't the case - if you, the player, had investigated it, there's no telling whether it would have been there to find, because its being there depended on the GM's whim. Hence while you can imagine your character investing their memory of the Cat Goddess statue with the structure of a yet to be discovered secret, you yourself can't do the same for your own memories of play - the experiences are structured differently, and so immersion in the sense of the analogy of experience you feel with your character is lost.

I just want to credit Idiom Drottning with an incredibly insightful point before going on to critique them. Their approach to gaming, the "Blorb", is entirely consonant with everything I've said above, and is a font of valuable insights. The specific one I want to highlight is that prep time is different to run time. This isn't just to do with how you can produce better, more detailed work given time to think - it's about how the players' experience will be different if they think something is coming straight from the prep vs if they think you're making it up on the spot. In theory this shouldn't matter; a common defence of the quantum ogre is that you could, as far as the players know, have prepped everything and fudged nothing. But what the players think you're doing (leaving aside the question of whether or not they're correct) does affect their experience of play. I hope to have contributed to shedding some light on this above, but all credit to the Blorb for codifying it into a set of principles before I typed a word.

The controversial point of the earlier Idiom Drottning post, which has already proven controversial in discussion of it, has to do with the "trust economy" that it sets up. This is the idea that trust between players and GMs (or between people more generally) is established via trust exercises, and then spent like a currency whenever a situation requiring trust manifests. This is where verifiability, and the thing of showing the players your prep, comes in; if a game fact is verifiable, then it doesn't "spend trust" (because the players don't have to rely on your word), so no trust is lost in the interaction.

As homespun epistemological frameworks go, I've definitely seen worse (I've marked a lot of undergrad Philosophy essays), but it doesn't strike me as falling in line with how we ordinarily think about trust. For one thing, trust is often assumed or given freely, most pertinently on the basis of expertise; I trust the plumber, or rather, the person who comes through the door claiming to be the plumber, to fix my boiler, without first requiring that they prove they know how to handle a wrench. In this sense, we should perhaps be open to giving the GM a "free gift" of trust, as the resident expert in the fictional world - a "trust fund", so to speak (all right all right, I'm sorry).

But the major point of issue is the idea of "spending trust". Ordinarily, we don't think of trust as transactional in this way. We do think of trust as being gained or lost - trust exercises and deceptions being respective examples - but it seems odd to speak of trust as being spent whenever a situation comes around that simply relies on trust. My trust in my geography teacher doesn't diminish with each fact about Venezuela that she tells me, even if I only have her word to go on. Assuming I don't independently verify her claims (thus validating my trust, and giving her a few extra trust credits), her continuing to teach me isn't by itself going to eventually erode my belief that she's telling the truth.

|

| This picture should be called "Trust Issues" |

This tells us that trust works like setting a bar. Events such as uncovering a deception can lower or raise the bar, but simply relying on it doesn't change its position - you can gain trust or lose it, but you don't "spend" it.

What does this mean for GMs? Well, I don't think you need to go showing players your notes - or rather, if you need to do that for them to trust you, you're in trouble. GMs can definitely lose trust, e.g.: by employing quantum tactics that erode player investment as detailed above. This doesn't have to mean getting caught (or fessing up that your game is completely improvised), but can simply mean failing to show players that their agency matters - that there are things out there that are undiscovered, and may remain undiscovered depending on what the players do. I can imagine a GM who frequently quantum-ogres their players having to resort to "See, I wrote it down! It's in the prep!", but by that point you're running to make up the trust you've lost, not just maintaining a net zero of "trust spent".

This is freeing for GMs, because there are times - especially when playing authentically - when the stuff in the prep doesn't cover the immediate situation, and you have to think on the fly. The Blorb actually covers how best to improvise in these situations, and does so very well. But provided you improvise consistently and impartially, no player trust is lost. The players may groan or grind their teeth if you foist a combat encounter on them, but if you have a solid foundation of trust, they probably won't even take the time to notice that you're improvising - they'll be too engaged with the situation, and what it means for their characters.

Players trust the GM to run the world, but running the world actually means having to improvise sometimes. It would be unrealistic for the GM to prep absolutely every detail for every eventuality. This is why things like hexcrawls contain mechanisms for producing content (random encounters, %-in-lair stats and so on), rather than rely on sheer volume of prep - but these mechanisms all leave the GM to connect up the dots and flesh out the details at the table. Hence part of trusting the GM is trusting them to fill in the gaps, and to simply do so in a way that fits with the world, rather than in a way that pushes the GM's preferred content on the players. There are long-running campaigns out there where the players trust the GM, without the GM ever having to have verified for them which details are prepped and which are improvised to "top up" their trust level.

(Compare, for instance, this post on how Classic Traveller was designed to be run almost entirely improvisationally, in the sense of the GM applying the mechanical results of random tables consistently and logically. This doesn't seem to diminish the belief in the world as a real place - on the contrary, the high degree of mechanisation in CT is one of its main draws, especially when playing solitaire, essentially the most low-trust gaming environment possible. CT is attractive because its emphasis on procedure lends weight and impartiality to the world, even though the procedures themselves involve a large amount of adapting generated content on the fly.)

Ordinarily (or perhaps ideally), as a GM, you start with a base level of trust from the players and, unless you do anything to betray or erode that trust, that level will at least remain, allowing the players to treat the world you create as real in the sense described in the previous sections. If you keep demonstrating to them that it holds up to reasonable scrutiny, and doesn't warp to negate their actions, the players won't leave the game of exploring the fictional world to start playing the game of guessing what's in your notes.

🕷

This could probably easily have been three separate posts, but each new point led me on to write further. I've been having half-formed ideas for years now about how to apply these areas of Philosophy to the tabletop, and this seems like a good point of ingress, perhaps to be expanded later. I remain grateful to everyone and anyone who reads my thoughts on such subjects, and to the fecundity of the OSR scene and its collective imagination.

Stay well,

-SQ

Comments

Post a Comment