Pacing #2: Tips 'n Tricks

Alright, I said a while ago that I'd post some tips for keeping up the pace of a game. This is something I know can be a struggle for GMs - even if you know you want to change up the pace, you can be left at a loss as to what to do to actually implement that intention, both in terms of how to actually alter the speed at which the game proceeds, and what to change it to. So here, contributed to the internet's memory banks, are a few things that I do to keep things moving. Practical tips ahoy.

🕷

Set the scope / Discern purpose: I already talked about how D&D works on a turn structure in the previous part of this two-parter. In summary, make sure you get a declaration of action from everyone involved in the scene before you start adjudicating actions. You'd be amazed at how much time this saves, and how it keeps players engaged. See, if you follow up a single player's action instantly, and keep following up their subsequent responses to the consequences, the other players eventually lapse into inattention, exactly as if you'd started playing out a little scene with only that player's character in it. (Proper action structure also means that some rules stuff that otherwise wouldn't work actually does.)

Keeping things ordered also forces people to be purposive in their action declarations. It's actually really easy to lose sight of this, but it's really useful. A lot of the time players state each little bit of their plan, rather than saying what the plan overall will accomplish. Like describing their character laying down each individual piece of metal equipment end to end in one of those Breath of the Wild complete-the-circuit puzzles, for instance, rather than saying "I lay out all my metal equipment end to end to complete the circuit." I believe that this comes from a suspicion that the DM will jump on their idea if they say outright what they want - what the purpose of the plan is. It's kind of a "Gotcha!" from the players' perspective - the feeling is that the GM will undermine any out-of-box thinking that disrupts their scenario or solves a puzzle in a way other than the intended one, whereas if you lock them into agreeing to every tiny bit of plan up to the big reveal, they can't easily back out of it without going back on a previous judgement.

|

| "I cast Discern Purpose!" |

🕷

Have a scene goal: Being purposive is important on both sides of the GM screen, but the GM themselves has to do it a little differently. You need to get a feel for what each scene is doing - what question it aims to resolve. The Angry GM has an article on dramatic questions that helps with this, but this isn't the only way to conceptualise it. Often, the question won't be clear from the beginning of the scene, and it can be difficult to think, while you're running everything else that's going on, about what it might be. As the GM, you have by far the highest cognitive load, and it's important to streamline your procedures to account for this (this itself gives a minor boost to game speed, as you spend less time figuring stuff out). So, as above, homing in on what the players hope to achieve in the scene is a good way of divining its purpose, and is something you should already be doing, so doesn't amount to an extra load. It's also player-directed, which is good, since allowing the players to determine a) what scenes happen and b) what pace they are resolved at is a good way of facilitating player agency, and making sure the players feel that (more on that below).

The point of working out what the scene is for isn't to push the players into a particular course of action or anything like that. In fact, if you're letting them tell you what the scene is for, you're already following their lead. Instead, it's to make sure the scene doesn't run over-long. Where the tip above means scenes proceed as quickly as they need to, this one exists so you know when to wrap the scene up. If you don't know the purpose of the scene, you won't know when to end it - any time you want to move on, it'll feel like you're curtailing the players' engagement, like they still want to hang around and do more stuff. But the secret is this: If you don't set a strong purpose for the scene, and you don't divine what the players' purposes are, then they are liable not to have a clue either - they're probably hanging around on the assumption that you're prolonging the scene because you have something else in mind for it, just like you are with them. This seems like a small misunderstanding, but it can eat up loads of table time, and kill the pace, especially if it's a recurring problem because you don't have procedures in place to frame scenes such that they have clearly defined ending conditions. Work out under what conditions a scene has fulfilled its usefulness, and you know when to wrap it up and move on.

🕷

The fifteen minute rule: I've workshopped this one a lot - it was originally going to turn up in the first post on pacing as the ten minute rule, but I've since reconsidered. It's not a rule I live by so much as something I've noticed myself doing, and extrapolated into a maxim. The maxim goeth thus:

FMR: Whenever a player declares an action, try to show the outcome of that action within, at most, fifteen minutes.

That... came out bigger than I wanted it. Oh well, it's seared onto your brain now!

So this already assumes you're working on the "get all the action declarations in before you start resolving stuff" schema from last time. Obviously, otherwise what would you be doing between action declaration and resolution? And it works best with the purposiveness points above, as I'll explain.

The FMR does a few things. First, it forces you to understand what your players want to get done, even in things like RP scenes (again, why I use this specific terminology here) where it can be unclear - typically, conversations have lots of goals, which shift at the micro scale from sentence to sentence. But if you can understand at the broader scale that your PCs want to convince the NPC that x, or bribe the guard to overlook a crime, or even find out more info about y, you know to show them the NPC's belief or disbelief that x within about fifteen minutes, and so on. And an important point here is that, at the end of the fifteen minutes, the NPC doesn't have to have made up their mind indelibly either that x is true or that x is false. What has to have happened, though, is that they have visibly swayed one way or the other - progress towards a goal, or progress towards a fail state, can be considered an "outcome" for the purposes of the FMR. The key is, you have to show it. In the example of convincing an NPC, it might be helpful to narrate, straight up, that "Gert seems warily accepting of x, although she isn't certain." The key is that the PCs then get an opportunity to re-engage to convince Gert to full certainty, or to call the job done and move on - there's no hanging around in the scene not sure of whether they're achieving anything or not, or how to do so.

I've sort of buried the lede here; the purposive dimension, the evolving theme of this post, is important, but it's not the most important upshot of the FMR. That is the feeling of agency the players get when you demonstrate the consequences that their actions have. As GMs, we spend a lot of time thinking about how the players can exercise their free will within our campaign - how we can encourage it, and to what extent we can channel it. But it can be hard for players to feel empowered to make choices that have real effects, even if they are, if the pace of the game doesn't show those effects in a way that directly links them to player action. The FMR works on the somewhat simplistic idea that there's a timer on this; if you wait too long between a player's action and its effects, their brain won't link the two together. The effect will end up feeling like a premeditated contrivance of the GM's, rather than something brought about by player agency. The way round this, then, is to make sure that there's no more than 15 minutes between the players pulling the trigger and the "Bang".

The FMR is something of a loose heuristic, obviously more suited to certain scenes than others. But don't be fooled into underapplying it. Take, for example, the scene where the PCs are going around the city looking for info about a stolen artefact. One player declares they're going to the tavern, one to the docks, etc etc. If the players have declared that they intend to investigate the artefact by looking and asking in various places around the city, they're effectively telling you their goal, and the individual actions they're taking to achieve it; asking at the tavern, snooping round the docks, and so on. And that tells you what resolution scale the players are thinking at; essentially, they're treating the city like one dungeon room. And that's fine - the key, then, if you don't have a reason to do otherwise, is to run with that scale, and resolve it action by action, just like a dungeon room. You wouldn't trigger a separate roleplaying scene (taking more than 15 minutes) for the rogue who wanted to unlock the chest, while the wizard waits to translate the arcane runes on the wall and the dwarf waits to see if they recognise the stonework of the pillars - you'd just narrate, briefly, to the rogue whether they succeed or fail, with some colour as to how, and maybe the opportunity for one or two brief follow-up actions.

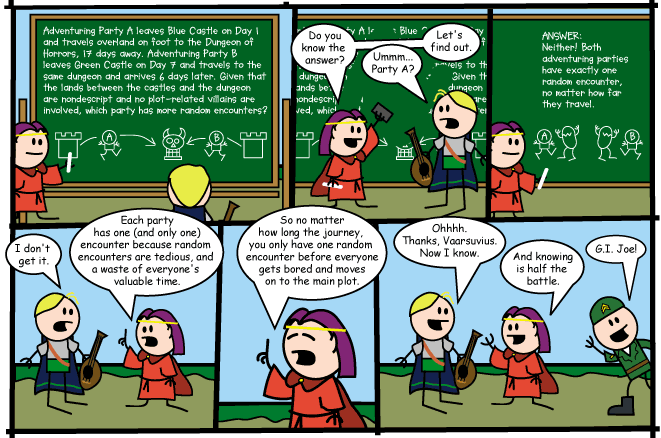

|

| Genauein encounters explained |

🕷

Okay, wrapping up. It's not enough to have player actions in mind, you have to keep checking in with their purposes. You can get a long way framing scenes at the widest resolution that will allow those purposes to be achieved. Don't leave too long between players telling you what they're up to and showing them how it turns out, or, through no railroading or any such fault, they'll stop believing that they can actually affect the world. And make sure you have a solid idea going into a scene, or soon after, what it will take to put the scene to bed. The same goes, by the way, for blog posts.

Comments

Post a Comment